There’s a hero inside each one of us. Each day we leave the safety of home and face the trials and tribulations the world has to offer. At the end of our journey, we return home changed by the experiences of our adventure. Finally, sleep takes us. This process begins anew tomorrow when we rise from the ashes. I believe that telling that story is an essential part of what makes us human. We can harness this seemingly universal story as an inexhaustible source of compelling CI in our language classes.

For many years, I’ve been awestruck by Joseph Campbell’s famous work The Hero with 1000 Faces. In this book, Campbell’s love for story shines through every page as he details numerous manifestations of the Hero’s Journey from across the globe and throughout the ages. The idea of a collective myth fascinates me, and reading this book led me to two important questions.

-

Why is the story of the Hero’s Journey so compelling?

-

How can I teach L2 using the Hero’s Journey and make it comprehensible?

WHY IS THE HERO’S JOURNEY SO COMPELLING?

So many stories throughout history are just a fresh take on the Hero’s Journey. Star Wars, for instance, follows the proper steps of the Hero’s Journey to a “T”. In Star Wars (the good ones), Luke Skywalker finds himself in the common world, is called to adventure, finds a mentor, faces challenges, confronts evil, and returns home changed.

I believe this archetype speaks to us on a deep level. There’s something about leaving the metaphorical cave (or our ancestors’ literal cave) and confronting the unknown. It’s a story that we seem to yearn to live out.

Obviously, many of us do not actively live out this story. But we do seem to enjoy watching other people live out the Hero’s Journey, as evidenced by the recent craze for superhero movies. Consider the following movies:

Black Panther

Avengers

The Incredibles

Deadpool

Ant-Man

Star Wars

Spiderman

Batman

Each of these superhero movies is a different manifestation of the same old story, changed only slightly to fit the context. The people in Hollywood don’t necessarily make the deepest films, but the people in charge of the story are not stupid, either. In general, they know what will pique the audience’s interest and what will maximize box-office sales. More times than not, this means the same old story (and I mean old) wrapped in a new package.

I’ve seen the same story of the hero capture my own son’s imagination. The film that first caught his imagination was Disney’s Moana. I love this film. It was incredibly well done and the story speaks to something deep inside my being. There’s just something primal about seeing a character leave home, go on an adventure, and experience personal growth as a result of facing her trials. Dr. Campbell didn’t live to see this particular animated film, but it’s just another version of the same old story. Moana would have fit perfectly in Campbell’s Hero with 1000 Faces.

As Campbell explains, the origins of the monomyth goes way back in history. And by that I mean waaaaaaaaaaaay back. It’s possible that our ancestors were communicating the message of this story before they had language. The hero leaves the safety of home, fights the dragon (or some other unknown monster) and returns home a changed person. It makes sense that this would have been the story for our ancestors, from virtually every (if not every) culture. The oral traditions of our ancestors were painstakingly passed down from generation to generation, being refined with each iteration. Clearly, the story still resonates with us and as it has has done for thousands of years. With that in mind, I can’t think of a better way to help my students learn to speak a new language than through the Hero’s Journey.

USING THE HERO’S MYTH TO TEACH LANGUAGES

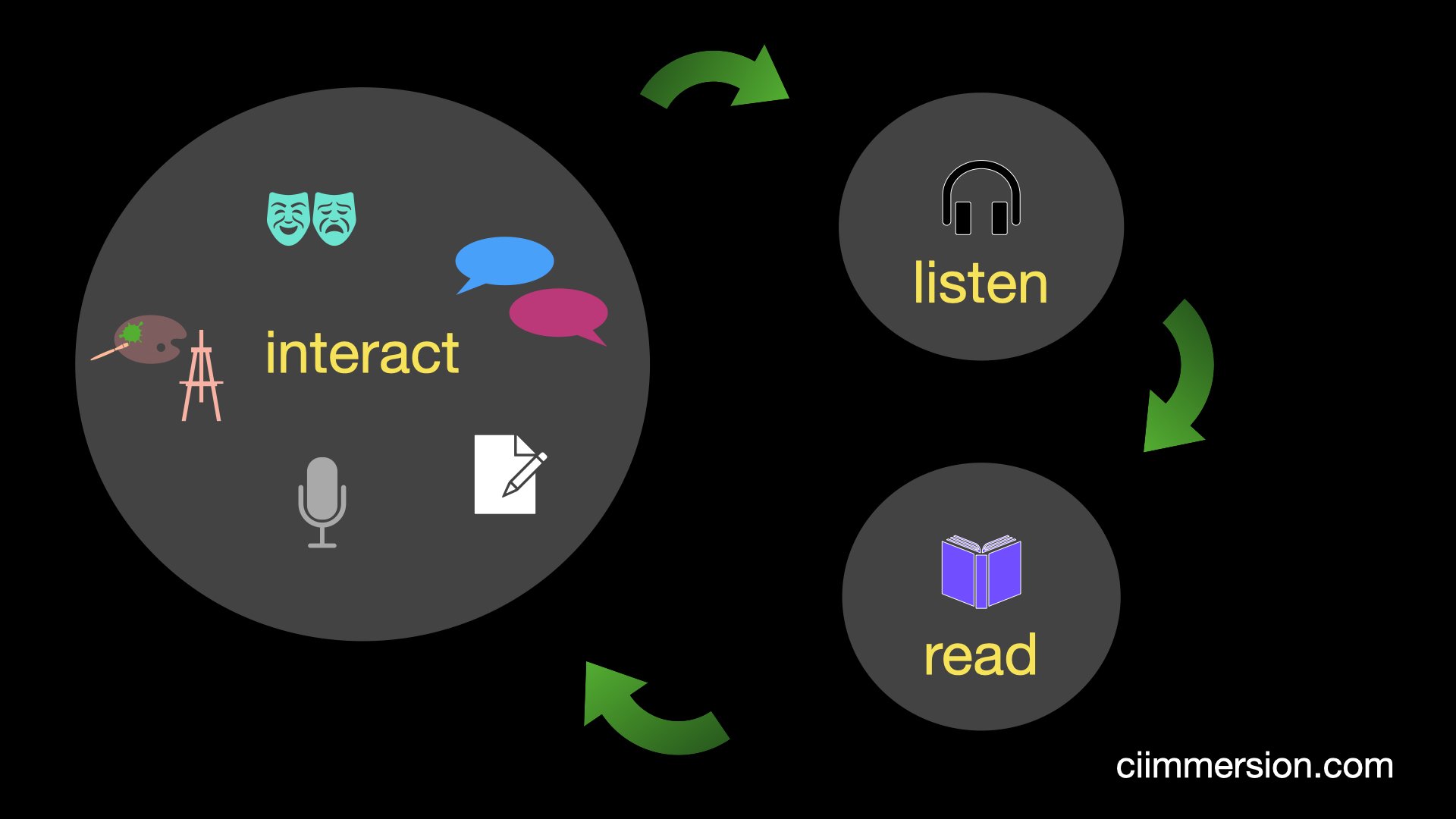

The thought of using a story that embodies the collective unconscious excites me as a CI Storyteller. This is a powerful and unique strategy to provide CI to learners in a context that way that will speak to them on a deep level.

One option would be to teach with “authentic” texts written for native speakers. Although the Hero’s Myth already exists in every language, we know that any text written for native speakers will be difficult to comprehend for learners, and especially beginners. The CI sweet spot is i + 1, or input the learners can easily comprehend plus a little bit of language they have yet to acquire. Instead of i + 1, a text written for native speakers is more like i + 100. This is akin to using full immersion to drown learners in incomprehensible input. Unless you want to spend the time and energy required to adapt the text to the level of your students, I am confident that “authentic” texts are not the answer to using the Hero’s Myth.

Using the CI storytelling process to co-create a level-appropriate text is the best solution. This means that developing a personalized Hero’s Journey for each class we teach. To accomplish this, we simply start out with a character and ask a million comprehensible questions that guide us through the steps of the monomyth.

By using the orbiting technique of asking circular questions, we can take into account the varying degrees of proficiency of each unique group of students. Each group of students is different, and we as instructors need to be sensitive to what they can comprehend and what they can’t. If they can’t understand it, we need to make it comprehensible before we move on.

A CI story created based on the Hero’s Journey could be extended across an entire term. Wouldn’t it be spectacular to co-create a novella with your students? Learners would finish the term and take home a personalized and meaningful epic story. Perhaps this would inspire them to continue their own language-acquisition journey, even after the course ended. Okay, that sounds marvelous (no pun intended).

The power of this story structure lies in communicating a compelling story in L2 that also happens to be comprehensible.

DEFINING THE CHARACTERS

At the beginning of the quarter, we begin by painting word pictures of three characters to help build listening comprehension and to actually do something useful with the language. For approximately 20 minutes per day for three consecutive days, we define three different characters that will appear in our personalized epic adventure. Each day we review the previous day’s character(s) and stretch them out before adding a new one. At the end of the three days, we are left with three detailed characters that we can refer back to and insert into various situations, make examples with, or compare and contrast throughout the quarter.

This part of the epic adventure alone is a goldmine for compelling CI. Sometimes I will ask about these characters during the normal short stories we co-create just as reference point for comparisons or to ask how one of them would respond in the same situation. It is a stelar way to keep L2 flowing in the classroom.

CHARACTER 1: THE HERO

This is the main character of the epic. Is it a man or a woman? What are they like? Are they tall or short? Are they smart or not? Is the person a superhero? What do they have? What do they want?

What the main character wants is the key to the epic, as it tells you so much about the character and drives the story forward. One character wants money, another fame, and another a family. In another class, the main character wants a to save his kidnapped wife.

The possibilities here are truly endless, and will change the timbre of our story dramatically. What the character wants leads the story in a unique direction and ensures personalization for each class. It helps determine if the story you co-create is going to be a comedy or a tragedy. All of these are fine, and the differences keep things from getting stale.

In one class the hero is a superhero. In another it’s just an ordinary person. The personalization is so much fun here, and letting the learners decide who these people are make the story as engaging as possible for that particular group of students. When the material is relevant to students, they will care about it and learn it by heart.

CHARACTER 2: THE HELPER

Our hero needs a friend, someone who can help her overcome the trials and tribulations on her journey. This character should parallel the main character. They should undergo a similar transformation, but perhaps in a different way. Maybe they want the same thing as the hero. Maybe they want something different. What do they want? Compare and contrast.

Having two characters is essential because it lets you use the “they” and “we” forms in your epic. These forms are criminally underrepresented in a language classroom.

Using these two characters in many different scenes also lets you compare and contrast. You could teach comparisons from the the very first week of [your language] 101 this way, and it would be entirely comprehensible. There’s really no need to wait until chapter 8 to do comparisons.

CHARACTER 3: THE VILLAIN

The antagonist of the story doesn’t need to be a villain, but it does help make it more exciting. The antagonist should want the same thing as the hero, which will create tension. During the Lord of the Rings, Frodo and Sauron both wanted the ring, albeit for different ends. Frodo wanted to destroy the ring of power, but Sauron wanted to wield it.

Maybe the antagonist of your story wants the same thing as your protagonist, in a negative way or for a negative end.

With three characters, it’s now even easier to do comparisons. The hero is brave, and the helper is as brave as the hero. The villain is a coward. The villain is the most cowardly of the three.

THE STORY

After the three main characters are defined, I move on to the story. We return here once or twice per week and will try to complete the story as we go through the quarter.

It’s the perfect activity to start the week since it’s listening heavy. When we have a short week (e.g. Thanksgiving), you can do this for the whole week and move the story along a bit more.

However you decide to break up this epic adventure, you’ll need to make sure to follow the proper steps to make sure students have maximum buy-in.

THE HERO’S JOURNEY STEPS

Step 1: The Ordinary World

Step 2: The Call to Adventure

Step 3: Refusal of the Call (optional)

Step 4: The Mentor

Step 5: Crossing the Threshold

Step 6: The Road of Trials – Tests and Tribulations

Step 7: Trials and Failure – The Helper

Step 8: Character Growth – The Helper

Step 9: Death and Rebirth

Step 10: Revelation and Change

Step 11: Atonement

Step 12: Receiving of a Gift and Return

Depending on the length of your course, you may want to condense the story. I do this by combining a number of the previous steps. For example, chapter one in this quarter’s Hero’s Journey may encompass Steps 1-2, chapter two covers steps 3-5, etc.

A BLEND OF STORYTELLING AND STORYASKING

We need to follow the proper steps in order to make a proper hero myth. There is a structure by which we must abide for students to accept the story. With this in mind, I bring a script into class with an outline of where the story is headed.

Since I want to make sure to include all the Hero’s Myth elements, it follows that a large portion of this adventure is a Storylistening Activity (a technique pioneered by Dr. Beniko Mason). For this portion of the story, students need only listen and try to understand what is happening. Get off your phones, put your laptops away. It’s story time.

I go out of my way to make the story comprehensible using visuals (gestures, drawings on the board, etc.), repetitive language, and limited vocabulary. I don’t want to drown anyone with the immersive input I’m providing them.

Of course, I want this to be a personalized story, so I also have many underlined portions of the text where students can change the events/feel/outcome of the story. This portion leaves room for more of a Storyasking experience, à la TPRS©.

The script keeps me from submerging learners and holding them under with too much new vocabulary. The underlined portions keep the story fresh and personalized to that particular class.

One quarter, my students and I began the quarter with an open-ended story. During a the first three days of storytelling, we defined the protagonist, a friend of the protagonist, and the antagonist. This took about 60 total minutes to accomplish, and was done entirely in Spanish. Through this exchange of me asking questions and the learners making decisions, they arrived at our Hero’s Journey premise:

Francisco lost his hair during a mad scientist’s (Andrés*) experiment. With the help of his friend Juana, Francisco tries everything in his power to get it back.

This premise is ridiculous. I think it’s the perfect way to bring up a variety of topics in context. Here is one possible tangent:

Me: Class, does Francisco comb his hair every morning?

Class: No.

Me: Why not?

Class: Francisco doesn’t have hair.

Me: Class, do I comb my hair every morning?

Half the class: Yes.

Other half of the class: No!

Me: I don’t?

One of the cheeky ones: No, you don’t have time.

Me: I don’t have time to comb my hair?

Same cheeky one: No, you’ve got two kids. It’s either comb your hair of drink coffee.

Me: Oh, that’s a good point. Class, I don’t comb my hair in the morning. I drink coffee.

Me: Class, who in the class combs their hair every morning?

This is an example, but not too far from an actual conversation I’ve had in class. The authentic and comprehensible interactions lead to more engagement, which leads to more input, which leads to more acquisition. It’s a virtuous cycle, and one that you don’t get from the textbook or legacy language teaching methods.

*Of course I’m a mad scientist

YOU GET A COPY! AND YOU GET A COPY! EVERYBODY GETS A COPY!

I keep track of each story and write it out as we go along. At the end of the quarter, I post the Hero’s Journey to our classroom site (We use the LMS Canvas), and students can download a copy for their reference.

I tell students that re-reading our story is a good way brush up for their final, since all the relevant grammatical and vocabulary items are in the story. I made sure of that when I wrote the script.

My hope is that students also refer back to this text with fondness as something they helped create in L2. They will be able to go back and read it whenever they want.

A DEEP DIVE ON CULTURE

I’ve been trying to come up with a way to incorporate more culture in my class. The Hero’s Journey is an easy way to sneak it in. Let’s say that my two o’clock class decided that the main character is from Colombia. Great. We can do a deep dive on that country (Do I smell coffee in my future?) by having the characters explore Cartagena, Cali and Bogotá. Each place a character goes is an opportunity to embed culture into our stories. Using embedded culture like this is the best way to teach culture besides physically traveling and getting to know these places in real life.

CONCLUSIONS

I am convinced that a properly-implemented and an appropriately-leveled Hero’s Journey is one of the best ways to deliver CI in the language classroom. If we want learners to get serious about reading fiction on their own in L2, this compelling introduction will help them learn to love doing just that.

As an aside, who doesn’t want that? Reading self-selected books in L2 exposes learners a wealth of CI they wouldn’t have seen otherwise. Furthermore, it will help them develop proficiency on their own, even long after they have left our classrooms.

If you haven’t read Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with 1000 Faces, I highly recommend it. This book helped me discover a new depth to the power of myth, and made me want to be a better storyteller. In his book, Campbell closely examines the stages that occur during almost every Hero’s Myth. I think it is required reading for anyone serious about getting better at CI storytelling.

I’m in love with the Hero’s Journey as a way of delivering CI to my students. It’s so open-ended and makes it easy to personalize the story for each specific class.