We know that comprehensible input is the driving force behind language acquisition. The more a learner hears and reads comprehensible language, the more opportunities they have to mentally and subconsciously process that input and convert it to intake — language that is ready to be acquired. Once at the intake stage, the brain either will or won’t acquire it, based on its own opaque criteria. It’s a bit of a black box and we have limited understanding of what is happening at that stage. Nevertheless, the takeaway is clear. Our goal as language educators should be to guide learners to the intake stage as often as possible. For the more often they reach intake, the more language they will acquire.

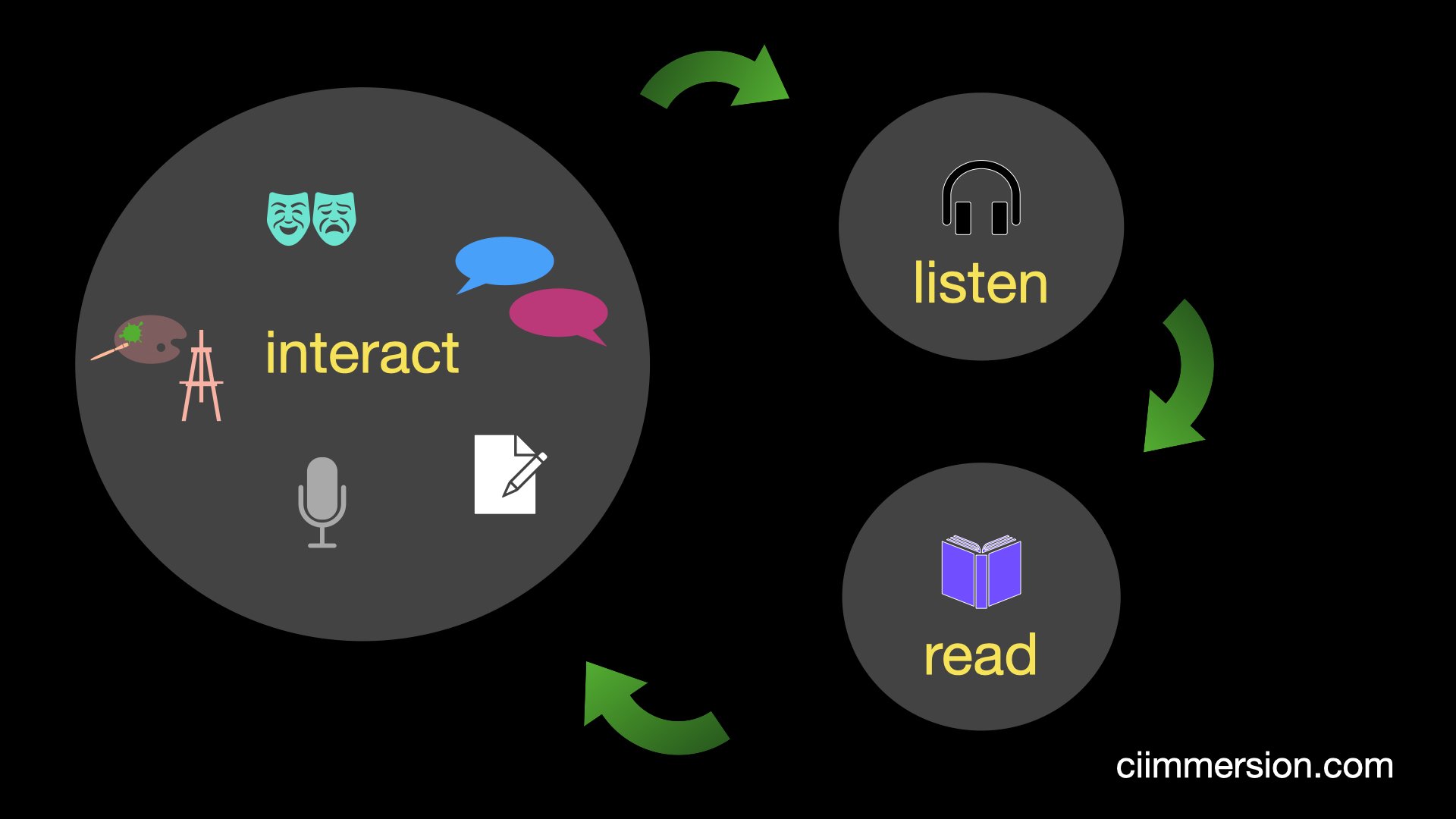

The aim is to consistently get learners to intake. To that end, we can rely on something I call a “Listen-Read-Interact Loop” (LRIL - pronounced “Laurel”). The idea is simple. The learner should listen and read to as much of the language as possible. Then the learner should interact with the language in some way.

The LRIL is a virtuous cycle. The learner hears and reads comprehensible language, and then interact with it in some way. This primes the pump for acquisition, and the learner is ready to start again. Slowly, the language the learner hears and reads should increase in complexity. She should hear and read things that are just beyond her level in order to get her in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Then she goes through the LRIL again.

Listen, Read, Interact. Listen, Read, Interact. On loop. Over and over and over.

A LRIL does not always have to go in order. Sometimes it will be Listen and Interact (L&I), and other times it will be Read and Interact (R&I). Whatever the case, interaction is critical to help learners convert input to intake. The interaction helps a learner make sense of the language they hear or read. Perhaps it provides the extra bit of processing time they need to fully comprehend the input.

Since input is the driving force behind acquisition, the interaction piece does not necessarily need to be linguistic output. This depends on a variety of factors, such as the level of the students participating in the LRIL. Learners might speak in pairs, draw a summary of an event, answer questions by writing complete sentences, take a survey, take a true or false quiz based on a reading, mark whether a statement applies to them, or silently act out a passage from a novel. These are just examples. The possibilities are limitless for what the interaction piece could look like in your classroom.

EASILY IMPLEMENT A LRIL

Interactive storytelling is a great way to get learners to jump into a LRIL. Learners listen to a small story fragment that I provide to them. Then I ask questions about the characters and events. They interact with the language by processing it mentally and answering my questions out loud. Once I am satisfied with their answers, they’re taking me, the story naturally drives us back to listening. I reinforce the pieces of the story they just created and lead us to the next logical statement in the story. This fragment gives them more time for listening, which leads to more questions from me, which leads to more interaction, and so on (See my post on orbiting for more details on this process.)

When a story is complete (or complete enough), I come up with my own interpretation of it. The next class period we look at the story again. After an oral retelling of the story, we read my version. Learners interact with the written language by answering questions based on the text. By the end of the class period, we’ve gone through dozens if not hundreds of LRILs.

CONCLUSION

Entering a LRIL is like winding a mechanical watch. Once you set the mechanical process in motion, the watch continues to tick until it needs winding again. Likewise, once the learner enters the LRIL, the internal workings of the mind take in the language and the mental model of the language unfolds to become more like that of a native speaker. Listen, Read, Interact. On Loop. Over and over and over.