Assessment

One of the most frequent questions I get about CI Storytelling is about assessment. There is so much work behind creating and grading assessments that it is unsurprising for The Beginning Storyteller to want or need some guidance.

In the field of SLA, most instructors are familiar with and use the traditional grammar test. Unfortunately, this does not mesh well with CI storytelling or other proficiency-based methodology. I was devastated when I first figured this out for myself, because it meant a complete overhaul of my assessments. Writing and grading assessments are my least favorite parts of teaching languages. Poco a poco, I developed various systems for measuring proficiency using assessments that are quick and easy to grade. We will explore the most useful ones a little later in the lesson, but first let us examine what is likely the current method of assessment in The Beginning Storyteller’s classroom.

Traditional Grammar Assessments

Traditional grammar tests like the ones I took in college and the ones I used to use in my classroom are not ideal for CI storytelling. Despite this, many storytellers still use them in their CI storytelling classrooms because they are department-wide tests, the instructor wants to see how storytelling measures up to legacy teaching methods, or for a variety of other reasons. The problem is that these tests were designed to assess consciously learned grammar rules and vocabulary, not proficiency. That’s why a student can ace a class that uses grammar tests, but not be able to speak at all.

It is a problem that learners pass our tests with flying colors, yet do not possess proficiency in the language. "I took four years of Spanish in college and got all A's, but I can't speak it." Hello, red flag. Four years of consistently delivered CI is enough to get extremely proficient in any language. If learners perform well on assessments but cannot produce at an appropriate level, that is an indication that something is wrong with the assessment. In the infamous words of Michael Scott, “Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me twice… strike three.”

Why do we insist on giving these tests that don't assess proficiency? I have some suspicions. First, I think it is likely that instructors already have a bank of tests, quizzes, essay prompts, etc. that rely on the grammarian mode of assessment. They think of all the work that went into making those materials and shudder at the thought of leaving them behind. It feels good to have those tests banked. This is the sunk cost fallacy. The time used to generate those materials can never be regained, but it does not mean that we are therefore bound to use them going forward. The reality is quite the opposite, especially if we take stock of our assessments and determine that they do not actually evaluate learner proficiency.

Another reason may be that we have become efficient and skilled textbook instructors. This allows us to teach directly toward a grammar test, since being a skilled textbook instructor and grammar tests go hand-in-hand. It is undeniable that a learner can acquire a good amount of language from a skilled textbook instructor. However, the problem with grammar tests as a mode of assessing proficiency is that knowing grammar rules does not equate fluency in the language. In fact, our mental model of language has its own set of rules that look nothing like the rules on the grammar test or that are in the textbook. Instead, our brains map the language based on input that it can understand, not via rule learning. Put another way, the rules of grammar are inferred at a subconscious level and not learned through explicit instruction.

I like to compare this with how we teach children. We don't start teaching children about nouns, and verbs, and adjectives, etc. until they are already in school, at which point they are astoundingly proficient in the language(s) they speak. Nobody assesses a two-year-old's language proficiency with anything resembling a grammar test. A few years back, our pediatrician wanted to assess the development of language in my children. “Do they produce sentences containing at least one word for each year old they are?”, she asked. That's the extent of concern the medical community has for the development of language in children.

Maybe the human development experts don't know enough. Maybe we should be giving our kids grammar tests to see if they can conjugate in the pluperfect subjunctive. It is a ridiculous premise on its face. Kids acquire when they are ready, and I believe it is safe to extrapolate this to teenagers and adults as well.

I'm not arguing that we want grammarless students leaving our classroom, but rather, we should give learners the best possible shot at increasing their proficiency in the language. That path is CI, and for The Beginning Storyteller, the vehicle is engaging stories. The way we assess proficiency is important, but not as critical as the actual facilitation of acquisition.

Finding the Right Balance for your Syllabus

Now that I have thoroughly trashed grammar tests*, my recommendation to The Beginning Storyteller is to not eliminate all your old assessments right away. In fact, I would leave most of them alone and just change one single assessment or kind of assessment per quarter/semester/year until you find a balance that you are happy with. A system that is in place is better than even the best alternative that has yet to be implemented.

If you’re going to use grammar tests, be sure to backwards plan. Take all the vocabulary on the test and incorporate it into stories. Orbit variations of each sentence that appears on the test to give learners plenty of reps. Also make sure to let students practice the kinds of activities the test will present them. Unfamiliarity is a big reason why storytelling students do not perform much better on grammar assessments.

*Notice how I am not trashing the instructors who use grammar tests. I used to use such assessments frequently, and there is probably still a place for them somewhere.

What Makes a good Assessment

Before we look at the ideal assessment and some There is no such thing as a perfect assessment. No matter how hard you try, you will not come up with a bulletproof assessment. Be sure to remember this as you create new tests, quizzes, and assignments for your class, as this message will help keep you from going insane.

Consider tattooing it on your forehead. “There is no such thing as a perfect assessment”.

There are many ways you can assess learners in a storytelling setting. It may be helpful to remember the reason we assess in the first place. In my estimation, the point of an assessment is to evaluate a snapshot of the learners' proficiency in L2. With this idea in mind, I require assessments to meet most or all the following criteria:

1. It must assess something specific. Avoid vague prompts. For example, the prompt “write three sentences about the future” might go into “Write two things you are going to do if it rains and one activity you are going to do if it is sunny”.

2. It must assess learner proficiency. That is, it must evaluate listening/reading comprehension or written/oral output. Naturally, testing comprehension is most important. Because CI is the driving force between acquisition, we want to be sure students are comprehending the language at a high level.

3. It must be easy to grade.

If you have 125 students and it takes five minutes to grade each assessment, that’s a grand total of 625 minutes – 10+ hours – of grading That’s too much time to spend on assessing anything in a language class. What if you were to make this a frequent task? What a nightmare! If you are in this situation, you probably already know that it is unsustainable. You will experience burnout if something does not change on the grading front, and an instructor whose passion has been extinguished helps nobody learn a new language.

I was in this camp when I first started teaching in graduate school. Instead of burnout, I chose to revamp my assessments. Currently, my most complicated assessments take two minutes or less to grade per student. Some of them are down to the 15-30 second range.

4. Ideally there is a rubric for easy assessment to take the guesswork out of grading.

5. In general, the results of the assessment must be similar across different student populations. For example, the results should be similar in different sections of the same class, in the same class with a different instructor, in the same class in a different year, etc.

Rubrics

Another way to systematize your course is to use rubrics — ridiculously simple rubrics.

In my estimation, most language assessments are too sensitive. What’s the difference between a learner who scores a 93% and a 94% on a quiz? I cannot imagine how detailed the rubric would have to be to attain such precision. The Beginning Storyteller should aim for a much blunter rubric, which is why I advocate for the “2, 1, 0” and the “4, 3, 2, 1, 0” rubrics.

My default grading scale is “2, 1, 0”. This is the perfect rubric for formative assignments, but you can use it for summative assessments as well. It is precise enough to give good feedback but blunt enough to be easy to grade. Be aware that this rubric will sometimes cause wacky things to happen in the gradebook, especially at the beginning of the term. But provided that there are enough scores in the gradebook, you will still get a nice average and your gradebook will play nicely. Here is the basic “2, 1, 0” rubric in all its glory:

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 2 | You did it easily. |

| 1 | You completed the task successfully, but you struggled your way through at times. |

| 0 | You didn’t attempt the exercise (absent, etc.) |

When you want more sensitivity, use ‘4, 3, 2, 1, 0’ is the scale. For example, I use this for story summaries and my final oral exam.

When you grade with these rubrics, you must be brutally honest. A “1” is not a bad grade in this type of scoring system unless there are only a handful of such assignments in the gradebook. I admit I avoided this kind of grading scale for a long time, opting instead for the traditional ten or 100 points for each assignment. When I finally tried these simpler rubrics, the ease of use and the fairness of this grading scale instantly changed my mind.

As I mentioned before, I was worried that my grades would be skewed heavily. However, after adding a bunch of assignments to the gradebook, I saw the grades start to normalize. I always end up with the expected bell curve for the distribution of grades across all my classes.

Assessments for Storytelling

Below is a list of possible assessments you could use for any story. Feel free to use any or all of them, but it is possible to over assess. I recommend limiting assessment to two of the following assessments per story, three at the very most.

1. Interpersonal Communication

2. Listening Comprehension Quiz

3. TPR Quiz

4. Timed-Write

5. “Yo puedo” / “I can” assessment

6. Oral Story Retell

Let’s go through them one-by-one in greater detail.

Interpersonal Communication (formative)

Building a good system for daily assessment is struggle for many language instructors. For The Beginning Storyteller, it can be hard to figure out the best ways to assess learners during the storytelling process. One of my essential assessments is called “Interpersonal Communication” (IC), and it fills this role nicely.

IC is a daily assessment that has replaced the “participation” grade in my syllabus. In reality, this is the way we norm students to set themselves up for success. The items assessed are the habits we want to instill in learners so that their affective filter is lowered and their focus kept on communication in the target language. Giving learners a grade for these behaviors rewards them for taking part in the communication process.

THE INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION RUBRIC

Every day I grade students on their attempt to communicate in L2 with other people. This might mean talking to a partner, a small group, the whole class, to me, etc. In my classes, each class period is graded using the following rubric:

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 2 | You were present and actively participated for the whole class period. You made your best effort to speak only Spanish (level-appropriate speaking/writing, ‘mistakes’ OK). |

| 1 | You were present but did not actively participate for the whole class period. You made your best effort to speak only Spanish (level-appropriate speaking/writing, ‘mistakes’ OK). |

| 0 | You were not present in class. You did not actively participate. You used English in class. |

You’ll notice that the only way students can earn a 0 is by not being present or by not being engaged. If they are there and trying to engage in the communication process, no student will earn less than a 1/2 for the day.

This rubric is powerful because it normalizes the class for storytelling. The rubric keeps the class in the target language, builds classroom community and is easy to keep track of. You know instantly who is doing all the right things to succeed and who is not. Moreover, assessing IC can be systematized into a once-per-week data entry task. Although this is a daily assessment, I enter in a cumulative score for the week. If we meet five times in a week, there are 10 possible points.

There are many ways to log IC, but I use an old-fashioned pen and paper to keep track. It is important to note that IC is not an attendance grade, although it is not possible to demonstrate interpersonal communication if you are not in class. Therefore, attendance is included in this grade only because we need some sort of observable sample to assess.

Listening Comprehension Quiz

Much of CI storytelling hinges on learners interpreting aural input. Therefore, assessing students’ assessing listening comprehension is a must for The Beginning Storyteller. The washback effect is real, and learners will tend to pay attention to the things we put on assessments. Including listening comprehension in our assessment strategy gives feedback to learners that listening is an essential skill. Fortunately, this does not have to be complicated.

One simple assessment you can give learners is a True/False quiz about the story you co-created or about a parallel version learners read. My procedure is as follows:

1. Read 6-10 sentences out loud, two or three times per sentence.

2. Instruct students to listen carefully and mark whether they think the answer is “cierto” or “falso”.

3. Have students exchange papers and get ready to grade each other’s work.

4. Read the sentences aloud once more and ask for a choral response from the class.

5. If the answer is false, have students help you correct it to be true.

6. Instruct students correct their partner’s quiz.

7. Be sure the quiz taker gets to see their score before it gets turned in to you.

I love this activity for several reasons. First, it assesses comprehension of the story we just worked on as a class and provides a window into the learners’ listening comprehension skills. If a learner was paying attention and actively participating, this quiz is a piece of cake. This creates a positive feedback loop that builds learner confidence over time. Furthermore, it encourages learners to pay careful attention in future stories, since they know that the information in the story could be on the assessment.

nother reason I like this quiz is that it is easy to generate. Simply looking at the text will give you more than enough true sentences that you can change to be false as needed. You could even have students write their own True/False comprehension quiz beforehand and pick your favorite to use for the class. Consider giving automatic full points to the person whose quiz you pick to incentivize the writing of good quizzes.

Lastly, this quiz is also easy to grade since students do that for you. You could do the grading yourself since you will have the answer key, but I find it beneficial for learners to participate in the grading process. They get additional comprehensible reps, and you guarantee they see the feedback on the quiz beyond the grade.

For me, listening comprehension quizzes fall into the “summative” bucket and the “quizzes” category in the gradebook. This works well because it allows learners to earn some easy points in a high-scoring category and affords them some wiggle room on more difficult assessments. If you make these formative assignments, be sure to include some sort of listening in your summative assessments.

Timed-Write

A timed-write is a great way to assess learner proficiency by getting a snapshot of their production in L2. The process is simple:

1. Have students take out a sheet of paper and a pencil. They should put all other materials away.

2. Set a timer for 5-10 minutes and have students write as much as they can in L2 for the duration of the timer.

Many students will try to stop and think too much, so be attentive and encourage them to keep writing the entire time. I prefer them to write a summary of the story we created, read, and discussed together, because it is easier for students to write about something they are familiar with. If you aren’t thrilled with the idea of a story summary, this could also work as a free write or on an assigned topic.

3. When the timer goes off, students add up the number of words they wrote and write it at the top of the page.

Students invariably ask what words count, and my rule of thumb is that English words do not count, but proper names and places do. I also do not allow more than two “verys” in a row. For example, in the sentence “I am very, very, very, very, very handsome,” the student could only count 2 “verys”.

The idea with the timed-write is to get learners to turn off their L1 brain as much as possible and let L2 bubble up from their subconscious. This will give you a snapshot of the learner’s true level of production. Five minutes is plenty of time to get the data you need. The task tends to expand to fill the time allotted to it, so clamp down on the amount of time you give students to finish it.

I use the following rubric for grading timed writes:

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 4 | 50+ words in L2, on topic, uses the vocabulary from class, easy to understand |

| 3 | 40-49 words in L2, on topic, uses the vocabulary from class, somewhat easy to understand |

| 2 | 25-39 words in L2, on topic, more-or-less on topic, uses the vocabulary from class, somewhat difficult to understand |

| 1 | Fewer than 25 words in L2, not written by hand, not on topic, difficult to understand |

| 0 | Missing, not the student’s own work |

If you make this a formative assignment, you can tell students that it will only be graded on word count in L2. Its purpose is to let students experiment with the model of language they have in their head. As a summative assessment, you should require that students stay on topic and use the vocabulary from class, though volume is the most important. For this reason, I still grade mostly on word count.

TPR Vocabulary Quiz

An easy way to assess vocabulary is via TPR, which is baked into the storytelling process. Each story includes 3-6 TPR phrases, and I add these to a running list that we review periodically when I teach new vocabulary This is the perfect source material for a TPR vocabulary quiz.

While other learners work on an independent activity (e.g., FVR*), have them come up to you one-at-a-time. Provide them with two sample TPR gestures from the list at random. Students must tell you the word/phrase in Spanish. Each word/phrase is worth 1 point, for a total of 2 points (2, 1, 0).

In terms of frequency of these assessments, you have some flexibility. For instance, you could do a TPR vocabulary quiz each week with just the three to six phrases to choose from. Alternatively, you could do such a quiz after a set number of stories, say, five or six.

* FVR Free Voluntary Reading

I can... / Yo puedo...

Having learners respond to specific prompts is a great way to assess proficiency. For this reason, I use “I can” assignments at 2-3 times per quarter as summative assessments to determine what level students are at.

After working with comprehensible stories for a good chunk of time, I want to document evidence of acquisition.

I have students pick a prompt from a hat (they have the all the possible prompts ahead of time), and they have to respond out loud for 30-ish seconds. For this I have students come up to me in groups of three. This way they have to present in front of some peers, but not in front of the whole class.

Another way to do this is to ask students to record a video of themselves expressing some ideas from the stories we co-create and read (more on this in the section below). With this approach, I give students 20-30 minutes to read a prompt, come up with answer, record their video, and get it submitted.

My school uses Canvas as an LMS, so leaners upload their video directly to Canvas, but you could have them upload to anywhere that makes sense. For example, you could have learners make a public/private YouTube video and have them email you the link. There are a bunch of ways for students to submit video, but my recommendation is to do a little experimentation and pick whatever option is easiest.

I love “I can” assessments because they are laser-focused on what they cover and are easy to grade. As soon as I’ve seen the video, the grading is done. In a nod to my lazy efficient nature, “I can” activities are graded 2, 1, 0.

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 2 | You nailed it. You completed the task with ease. You were able to respond to the prompt with accuracy, confidence, and without long pauses. |

| 1 | You completed the task, but you struggled your way through it. There was some hesitation in your speech. You were lacking in confidence to the point that it affected communication. There was enough inaccurate language that it was difficult to understand. |

| 0 | You didn’t complete the assignment, didn’t follow the prompt, used Google Translate, read your response off a sheet of paper, etc. It could also mean that you didn’t turn in the assignment on time or there was no video. |

DEVELOPING “I CAN” ASSIGNMENTS

Read through your story script before you begin teaching it. Pick three concrete things related to the story you want your students to be able to say when you’re done with the week. In the story we analyzed in the previous lessons, one theme was working/jobs. In this example task, I want students to be able to express the following ideas:

1. I can say where I work and if I like my job. If I don’t have a job, I can say that I don’t have a job.

2. I can name two places I want to work.

3. I can name one place I don't want to work.

Because I only use “I can” assessments sparingly, I will give students three or four possible prompts and randomly assign one to them on the day they record their video. My LMS does the choosing for me, so different students end up responding to different prompts.

I systematize this by coming up with one “I can” prompt per story that we tell. That way I already have a bank of them ready to go when the time comes.

Oral Story Retell

Perhaps the simplest way to assess proficiency is through Oral Story Retells. For this assignment, learners retell you a story that they read on their own or co-created in class. It is a perfect capstone assessment for learners because it assesses comprehension and oral proficiency. It is also agreeable for The Beginning Storyteller because it involves zero preparation on your part, and you will be done grading it as soon as the learner is done telling it. All you have to do is listen and take notes – the rubric does the rest.

After students have completed the test, you ask questions about them that are related to the story they retold. For example, let’s say that in the story a character goes to a café and drinks a coffee. You may ask a student something like, “Do you drink coffee?”, “Do you prefer coffee or tea?”, or “What do you drink when you are thirsty?”. This provides a way to assess their conversational ability during a spontaneous interaction. You can prepare a list of questions ahead of time if it makes you feel comfortable, but it is not necessary. Instead, I recommend that you take them from the text itself.

I use this assessment as my final exam, which is usually a 2-hour block for me. When I finish with the block of tests, I am mentally exhausted from listening to all retells, but I’m done grading. Remember that efficiency and ease of grading are hallmarks of a good assessment.

My rubric for this assignment is as follows:

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 4 |

Student demonstrated above-average Successful communication of a specific message in Spanish. Student responded fluently to all the instructor’s questions using above-average emerging output in Spanish. Student demonstrated above-average understanding of relevant vocabulary. Student demonstrated above-average production of grammatical forms, especially those covered in class. Student demonstrated a high degree of confidence while speaking and interacting in Spanish, which was highlighted by few (if any) pauses. Use of Spanish filler words such as “bueno” “pues”, “este”, etc. |

| 3 |

Student demonstrated level-appropriate communication of a message (i.e., the events of a story) in Spanish. Student responded to most questions using level-appropriate emerging output in Spanish. Student demonstrated level-appropriate understanding of relevant vocabulary. Student demonstrated accurate production of vocabulary and grammatical forms, especially those covered in class. Student demonstrated adequate confidence while speaking and interacting, which was highlighted by a lack of hesitation in Spanish (e.g., few pauses and very infrequent use of “ums,” “uhs,” and/or other English filler words). |

| 2 |

Student demonstrated limited communication in Spanish. Student responded to some of the instructor’s questions freely using emerging output in Spanish that approached the expected level. Student demonstrated some understanding of relevant vocabulary. Student demonstrated accurate production of relevant grammatical forms below the expected level. Student demonstrated a lack confidence while speaking and interacting, which was highlighted by some hesitation in Spanish (e.g., some long pauses. Many “ums”, “uhs”, and/or other English filler words). |

| 1 |

Student could not communicate in Spanish. Student could not respond freely to instructor’s questions using emerging output in Spanish. Use of English. Student did not demonstrate understanding of relevant vocabulary. Student did not demonstrate natural or accurate production of grammatical forms, especially those covered in class. Student demonstrated a lack confidence while speaking and interacting, which was highlighted by frequent and long hesitations in Spanish (e.g., long pauses. Many “ums,” “uhs,” and/or other English filler words). |

| 0 | Student was absent, made no attempt, or did not do their own work. |

Each category in this rubric has three main components. Let’s break them down.

COMMUNICATION AND FLOW

Communication is the most important factor that I look for when grading this assessment. I want to hear students being able to communicate the events of a story using only their emerging output in L2. This does not mean to look for perfection, but if the learner can successfully communicate the events of the story. Accuracy is part of that, but does not make up the whole of the grade.

GRAMMAR AND VOCABULARY

This is another one of the few times in my course that you should evaluate grammar in context. Students have been afforded the opportunity to study the story ahead of time and bring in picture notes. Looking for their grammar and vocabulary to be accurate but try not to be overly critical. Despite the generous design of this assessment, it is still incredibly difficult for some learners to remember everything.

NATURAL PROGRESSION OF FLUENCY

It is impossible to learn to speak a new language overnight. Nonetheless, you should see improvement over time. One such area is in fluency, or in connectedness of speech. Over time, the expected course of acquisition should make it easier for learners to string words and sentences together. Make note of this and refer back on future assessments to gauge this natural progression.

ALLOWING NOTES

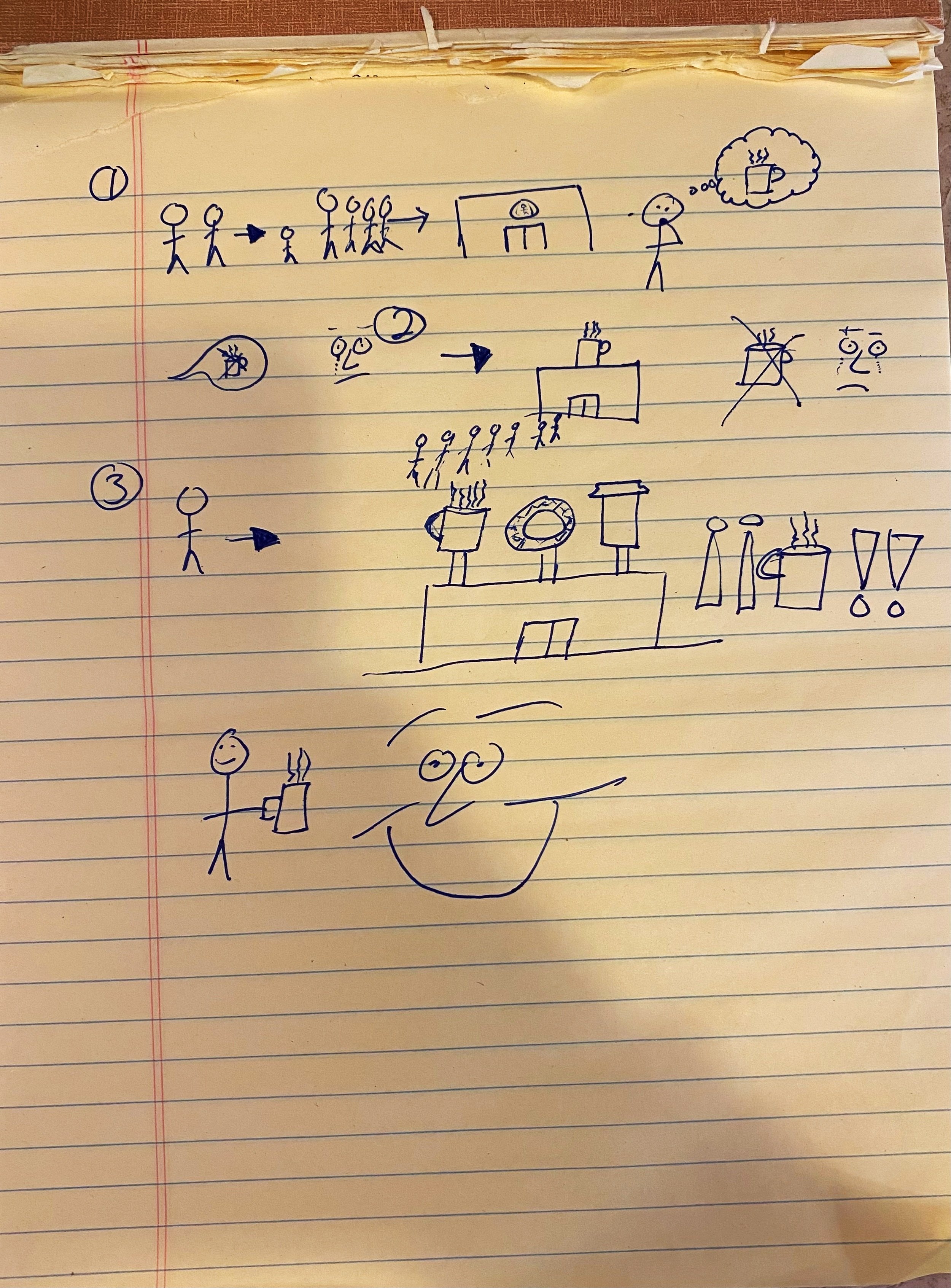

One question that will inevitably come up is if students can use notes on this assessment. I allow students to use picture notes during their retell with as many hand-drawn pictures as they like. This means they can draw one picture for each word or even each syllable if they want.

Hand-drawing picture notes has at two primary benefits. First, it guarantees that learners read through the text at least one more time before doing the retell. They can then use their picture notes as their “text”. While studying, they can return to the actual words to check how they fared. During the assessment, they will have the personalized “text” they created and rehearsed with. In this way, students can focus on how to express themselves instead of being pressured into recalling every detail of the story from memory.

The other main advantage of picture notes has to do with recall. The physical act of drawing the pictures to represent the text ties the meaning of the L2 words to the pictures. Much like with TPR, it will be easier for learners to remember the vocabulary when they see their unique hieroglyphs. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this seems to short circuit their L1 brain and allows for better recall in L2.

The only caveat to these notes is that, for the notes to be permitted during the assessment, there can be no words on the paper. The point of this assessment is not to measure how well a learner reads out loud in L2, but rather their comprehension of the text and their oral production.

The picture notes are not required, but maybe they should be. Students who take the time to draw out the story tend to perform way better than those who just try to memorize or remember everything without notes. If they draw enough pictures, they always remember how to say something, even if it is not perfectly accurate.

IN GROUPS OR INDIVIDUALLY?

Before you assign this task, you need to decide if you want to test in groups or individually. I have done both, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

If you have students test individually, it affords a great opportunity for giving learners feedback. However, it takes way longer to administer. I also get the impression that some learners may be intimidated talking to the instructor one-on-one.

You will finish the assessment faster if you put students in groups of two or three. Furthermore, you will see interaction between the learners, because they have to listen to each other to pick up where the other left off.

In this scenario, I recommend that you pick the groups. This will allow you to pair learners with a similar skill level. Many students are much better at telling the first half of the story, so keep that in mind when it comes to picking who goes first, second, and third (if applicable).

If you select the group retell option, I recommend that you also pick the story for learners. and they don’t know which half of the story they’re going to retell. If you let students pick which story they will retell, you need to know ahead of time which story each learner prepared. In this way, students who studied “Story A” can go with other students who also studied “Story A”.

IN FRONT OF THE CLASS OR IN PRIVATE?

Many students feel anxiety speaking in front of their peers. While we do want them to be able to speak in public, the best way for them overcome that natural fear is to do so voluntarily. The idea behind this assessment is to see what students can produce and talking in front of the class on a test does nothing but raise the affective filter. The test itself is enough anxiety, even though the aim is for it to be as low-pressure as possible.

Therefore, I recommend doing this assessment in a semi-private setting. The current individual or group sits around your desk to do their retell, while the rest of the class waits in the hall until they are called into the classroom. Alternatively, you could assign the other students a different task that must be completed by the time the class period ends.

Lowering the affective filter is key to getting an accurate assessment of learner proficiency. Therefore, I cannot recommend doing any sort of impactful assessment in front of the class.

Dropping Assignments

One ridiculously useful tip is to drop the lowest-scoring grade in each category. “How can I make up assignment ‘x’?”, is a question you have probably heard a million times. Dropping the lowest-scoring grade in each category makes this question almost disappear entirely.

I say “almost” because it never really goes away, you just have an easy answer: “Oh, there are no ‘make-ups’, but your lowest score in that category will automatically be dropped. This one can be your freebie.” If your class meets for an entire school year, I recommend dropping the lowest score from each category once per term.

Lesson 6 Worksheet

Get more out of this lesson by completing its companion worksheet .