Telling the Story

Story Setup

Before you begin the actual telling of the story, there are a few things you can do to be as prepared as possible. Let us briefly examine three of them before getting to the main course of storytelling.

TPR PART II

Total Physical Response (TPR) is foundational for learners and The Beginning Storyteller. A powerful technique for tying meaning to a physical gesture, TPR helps learners create and deepen mental pathways that lead to acquisition. Learners who use TPR as they became familiar with the vocabulary tend to have incredible recall1. For The Beginning Storyteller, TPR is scaffolding to be able to tell more complex stories.

There is some debate among comprehension-based instructors about how many phrases and words to teach with TPR. When I was starting out with Spanish, we used long lists of vocabulary that came from pre-written stories. This worked fine, but it required a lot of time spent going over vocabulary in class. These days, most people agree that this is not the most efficient use of class time. Instead, I recommend selecting 3-6 phrases from a story that I pre-teach with TPR.

Let us pretend that you are going to teach the following words and phrases via TPR using the steps outlined below:

she is nervous

s/he wants to be

s/he has a difficult test

s/he thinks

s/he has to go

I'm sick

1. Project or write the first word or phrase on the board.

Show a gesture that captures the meaning of the word or phrase.

The physical movement is important for building the mental pathways, so ask learners to show you the word as they learn it. They can repeat it out loud if they want, but it is not required.

2. In the past, I have had students make up gestures as a class. This is fun and personalizes the class but will take a bit more time. It is advisable to have some gestures in mind before you begin so you can quickly make one if the class draws a blank. It does happen, so be prepared.

3. Move through the list and repeat the steps until you have class gestures for each word or phrase.

GENERATING ARTWORK FOR THE STORY

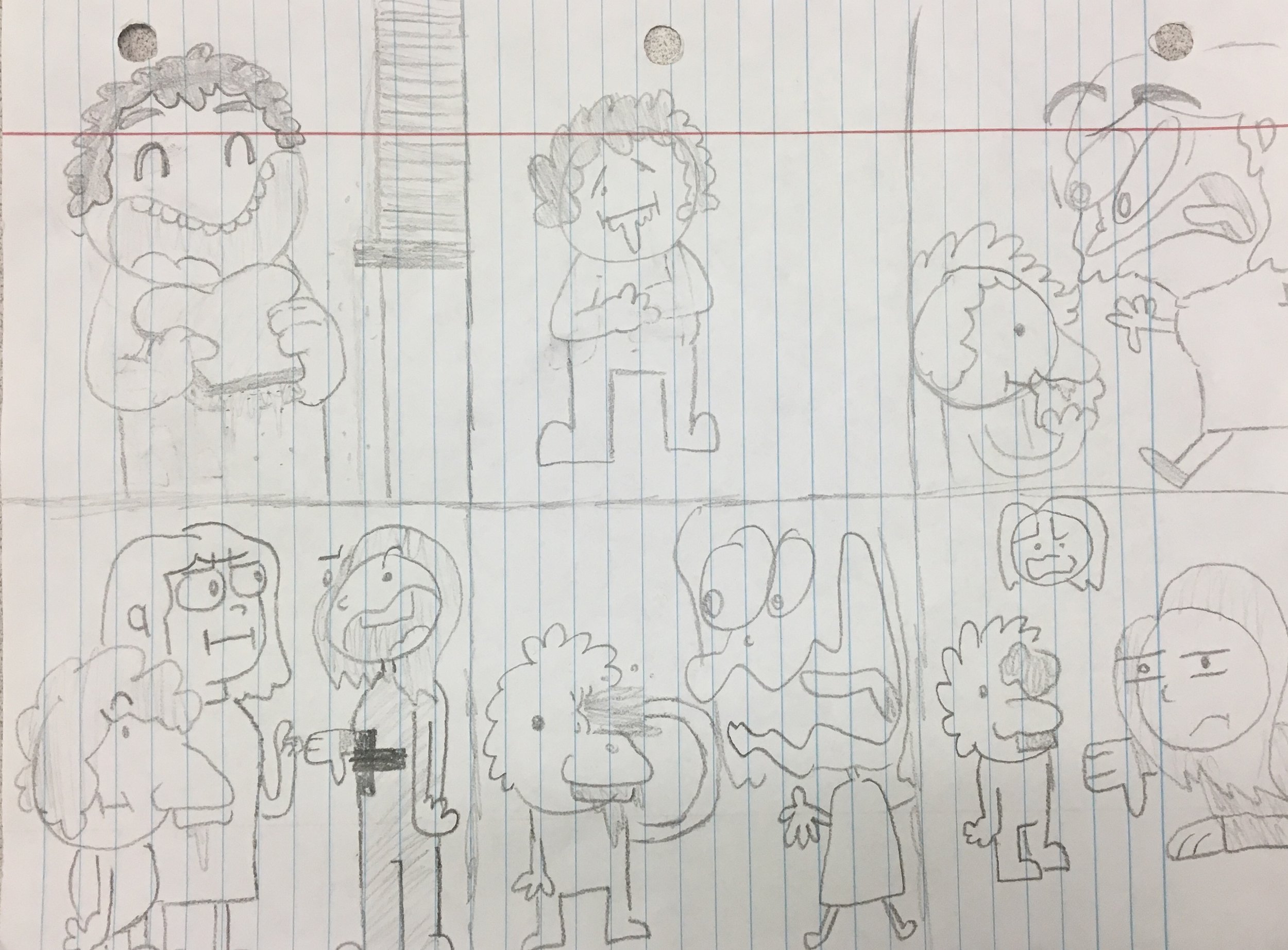

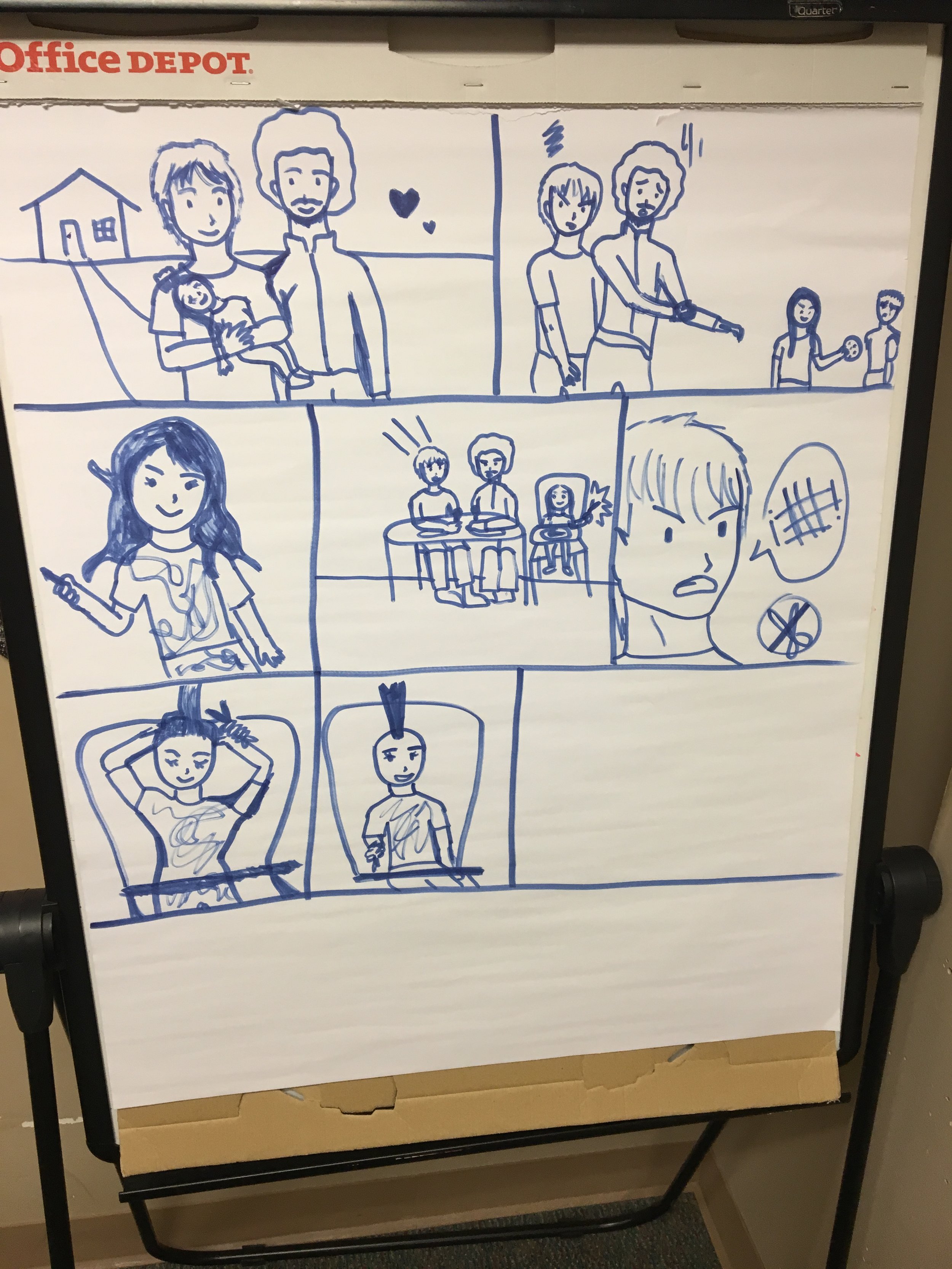

Before we begin the story, I usually assign a class artist. This person's job is to listen carefully during the story creation process and to draw a comic-strip version of the story. We will refer back to this artwork frequently throughout the week as we retell the story. Furthermore, the artwork will help us all remember what was happening in the story when we left off on the previous day.

The artwork serves other functions. Students can use it as notes to refer to during written story summaries or oral story retells. It also gives us a visual record of a story we told together when we finish the story. It is something we could pull out as a review sometime down the road as an intentional spaced repetition.

When I was a Beginning Storyteller, I instructed the class artist to draw six boxes on a standard 8.5" x 11" (A4) sheet of paper. Then as the creation process unfolded, they simply had to draw what they heard as best they could. In this version of the class artwork, I used a document camera to display the artwork on the screen while summarizing the story as a class each day.

In the latest iteration of this system, the artist uses giant sticky notes and colorful markers to make their drawings. I just stick the note to the board instead of using the document camera, which I find to be much simpler. Simplicity is the hallmark of an elegant system. Whichever way you choose to display the artwork is perfectly fine. The point is that you have a student-created visual aid that will help you deliver more CI.

At the end of class, the artist turns in the artwork to me and, depending on the size of the artwork, I do one of two things. If it's the giant sticky, I roll it up and place it neatly in a safe spot for tomorrow. If it's on a standard sheet of paper, I keep it in a folder I have for that particular class. This system prevents us from losing the artwork if the student is absent the next day. If the artist is sick, on vacation or whatever, I can just hand the artwork to someone else to pick up where the original artist left off.

Sometimes you will get some incredible artwork from these drawings, and often from students you would not expect to be so artistic. Showing off the talents of your students is a huge bonus to using learner-generated artwork.

KEEPING A RECORD

Storytelling has a lot of moving pieces. If you have more than one section to teach, it can be a juggling act to keep all the details straight. Even if you only teach with one story, it's easy to jumble up the different character names, plots, etc. It is helpful to assign a student to write down the story for you or to summarize the story in written form at the end of class.

When I was a Beginning Storyteller, I assigned a student to write out a summary of what we co-created. This worked well, but I still had to type up this story summary and give it a good amount of polish. Over the years, my system has become more efficient. Instead of relying on a student to write the summary, I set aside five minutes at the end of class, and we summarize as a class. As we go, I type up the summary in a Word document that I project on the screen. This lets me continue getting comprehensible reps with students while saving me the trouble of typing up a first draft of the story later.

Telling the Story: A Deep Dive on Orbiting

Orbiting, often referred to a circling by CI storytellers, is the most important skill for The Beginning Storyteller. For this part of the lesson, we are going to tell an example story using a sample script. The point of this exercise is for you to see orbiting in actions and how a series of questions can drive forward the narrative of a story to 1) provide way more CI than legacy methods, and 2) keep students engaged by the game-like nature of storytelling.

Sometimes as we go through this story, I will have the sentence "how do you say ____ in [Spanish]?" I'm going to use [Spanish] throughout this story because it's the language I teach in an official capacity. I will put it in brackets. That way, if you teach another language, you can mentally substitute your language whenever you see [Spanish].

Sara is from Mexico. She lives with his parents and his brother in Mexico City. She is young. She's 18 years old. She is a student at the university. She wants to be a doctor. This semester, she has three classes. She has a chemistry class, a history class, and an anatomy class.

On Friday, Sara is at her house. It's 7 o'clock in the morning. She thinks: Oh no! I have to go to class... Sara is nervous because she has a difficult test in anatomy. I don't want to take the test, thinks Sara. She needs to think of a good excuse. She thinks and thinks. Finally, she thinks of a good excuse: She can't go to school because she is sick.

Sara takes out her computer. She writes an email to her anatomy professor:

Dear professor,

I can't go to class today. I am writing this message from the hospital. I am very sick. I can't take the test today. Thank you for understanding my situation.

Attentively,

Sara

To begin, simply say a sentence that will get your started. In our case, we're going to use the phrase: "There is a young woman".

Instructor: There is a young woman. Class, is there a young woman?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Is there a young woman or an old woman?

Class: A young woman.

Instructor: Is there an old woman?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, there's not an old woman. There is a young woman. What's the young woman's name?

Billy (a student): Susan.

Instructor: Susan? Is the young woman called Susan?

*Crickets*

Instructor: Class, the young woman's name is not Susan2. What's the young woman's name?

Petra (another student): Anita.

Instructor: Anita? Is the young woman's name Anita?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Ah, yes. You're right. The young woman's name is Anita!

Instructor: Is my name Anita?

Class: No!

Instructor: No, my name is not Anita. My name is Andrew. Is my name Andrew or Anita?

Class: Andrew

Instructor: Oh, that's right. MY name is Andrew, the young woman's name is Anita.

Instructor: Where is Anita from?

*Crickets*

Instructor: Is Anita from Mexico3?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, she's not from Mexico. Where is Anita from?

Justine: Austria.

Instructor (playing dumb) 4: Anita is from Australia?

Justine: Austria!

Instructor: Oh, Anita is from Austria. Am I from Austria?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, I'm not from Austria. Am I from Australia?

Class: No.

Instructor: I'm not from Australia.

Justine (annoyed): No.

Instructor: Justine, I'm not from Australia?

Justine (more alarmed than annoyed now that she's the center of attention): No.

Instructor: Class, Justine is right. I'm not from Australia. I'm from Washington state. I'm from Walla Walla, Washington5.

Instructor: Who is from Austria?

Class: Anita.

Instructor: That's right. I'm from Walla Walla, Washington, and Anita is from Austria.

Notice at this point we are only one line into the story script. Look at all that CI! We've asked and answered more than 15 questions based two statements. In all honesty, you will need at least two days to go through a story script this way. Let's continue.

Instructor: Where does Anita live6?

Instructor: Does Anita live in Vienna?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: That's right, Anita lives in Vienna.

The powerful thing about orbiting is that you can use the gravity of different sentences to slingshot your CI spaceship on long tangents. Say you want to discuss Vienna more in this story. Just start saying sentences about the city and asking questions. Sometimes you'll come across an answer you don't know. That's why Wikipedia exists, and the article about Vienna is probably in the language that you teach.

Instructor: How many people live in Vienna.

*Nobody knows*

*The instructor does a Wikipedia search on Vienna in L2*

Instructor: Approximately 3,000,000 people live in Vienna. Is it a big city?

Class: Yes, it's a big city.

Instructor: Is Vienna the capital of Austria?

*Nobody knows*

Instructor: Yes, it's the capital, people!

I generally don't like to detour too much when telling stories, but an occasional detour will permit a deeper dive with an excuse to continue the flow of CI. It's also the perfect place to "teach culture" in context. After learning some things about Vienna, let's get back to the story.

Instructor: Whom does Anita live with?

Bethany: She lives with her mom.

Instructor: She lives with her mom?

Frank: How do you say “grandma”?

Instructor: “Grandma”

*Instructor walks over to the board and writes down "grandma" in L2*

Instructor: Does Anita live with her mom or her grandma?

Frank: Grandma

Bethany: Mom.

Instructor: Bethany says that Anita lives with her mom. Frank says that Anita lives with her grandma. Class, what do you think? Does Anita live with her mom, or does she live with her grandma?

Half the class: Mom.

Other half of the class: Grandma.

Instructor: Class, I know the answer! Anita lives with her mom and her grandma!

Combining these two student-generated answers makes sense in many situations. In this way you can validate both Bethany's and Frank's input and make a decision that will allow you to continue the story. One of the keys for The Beginning Storyteller is to not get hung up on the details for too long. Our goal is to sustain the flow of CI and, honestly, it is just not that important to know with whom our character lives. More important is the teaching of family vocabulary in context. If we skip the word for "grandma" in this story, we can always cover it in the next one.

Now that we have three characters, we can start comparing them.

Instructor: How old is Anita?

Bethany: 25.

Instructor: Is Anita 25?

Frank: 85!

Instructor: 85?! Anita can't be 85! She's young!

Frank: Oh, yeah! She's 22.

Instructor: Is Anita 22?

Petra: Yes, she's 22.

Instructor (looking right at Frank): Anita is 22 years old. How old is Anita's grandma?

Frank: 85!

Instructor: Yes! That's right. Anita's grandma is 85. Is Anita 85 or is her grandma 85?

Class: Her grandma.

Instructor: That's right, her grandma is 85. How hold is Anita?

Class: 22.

Instructor: Anita is 22 and her grandma is 85. Anita is 22... Am I 22?

Billy: No, you're 85.

Instructor: I'm 85?! I'm not 85! I'm young. How old am I?

Bethany: 25.

Instructor: Class, Bethany says that I'm 25. You are very smart, Bethany.

Billy: You're 85.

Instructor: I'm not 85, I'm 25. Bethany says that I'm 25. Am I young or old?

Class: Old!

Instructor: No, I'm not old! I'm young! Let's practice. Am I young?

*Instructor signals the class to repeat*

Instructor and class together: Yes, you are young.

Instructor: Good, that makes me happy. I am young and Anita is young. How old is Anita

Class: 22.

Instructor: That's right, Anita is 22. And her grandma is...

Class: 85.

Instructor: Perfect, Anita is 22 and her grandma is 85. Excellent work.

Even though it is not in the script, you can add as many details as you want to about Anita. Sketching out a detailed description of Anita will teach basic descriptions and make your main character more interesting. These details might come in handy later for explanations as to why a character does certain things. For instance, a smart character would probably do smart person things later. Let us see if the students decide to make Anita smart. In my experience (and I have no clue why this is) they typically make the first character we create together be... not smart.

Instructor: Is Anita smart?

Bethany: No.

Instructor: Anita is not smart?

Class: No.

Instructor: Oh boy.... Class Anita is not smart. Is Anita dumb?

Frank: Yes!

Justine: No, she's not dumb. Just not very smart.

Instructor: Okay, fine. Poor Anita. She is not very smart. You are all smart. You all study [Spanish]. You all are very smart. Am I smart?

Frank (cracking wise): No!

Instructor: Wait a second! I am smart! I'm very smart. Let's practice. Class, am I smart. Let’s try that again. Am I smart?

*I cue them to repeat after me*

Instructor: Yes, [professor Snider], you are very smart.

Class: Yes, [professor Snider], you are very smart.

Instructor: Ah, thank you. I am very smart. Is Anita very smart?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, Anita is not very smart. I am very smart, but Anita is not very smart.

You do not always have to ask another question to drive into a new sentence to orbit. Once you feel the wind start to leave your questioning sails, you can simply move on to a new statement. In our story script, the next line is not an option, since we want to target the names of different academic subjects in our story.

Instructor: Class, Anita is a student at a university. Is Anita a professor or a student?

Class: A student.

Instructor: That's true, Anita is a student. Am I a student?

Class: No.

Instructor: I'm not?

Class: No.

Instructor: I have a confession. Class, I am a student.

Class (indignant): No!

Instructor: I am a professor of [Spanish], but I am a student of French.

This bit is great for getting more "I" reps. But now you can ask some orbiting questions about a student you pick from the class. Normally this is someone who "gets it" and is willing to play the conversation game with you.

Require that they answer in a complete sentence, since you want to model conversation. This person may answer in a way that a non-native speaker would not, and that's fine. You just want their raw language, and you can help them if need be. They are just answering with the subconscious mental language system they have developed to this point, and it is natural for their interlanguage looks a lot more like L1 than L2 at this stage of the game. With that in mind, it is necessary to be extra helpful, patient, and understanding for this person.

Instructor: Bethany, are you a student?

Bethany: Yes.

*Instructor indicates with a hand gesture that they want more information*

Bethany: Yes, I am a student.

Instructor: Class, Bethany is a student. Am I a student?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Am I a Spanish student?

Class: No.

Instructor: Am I a French student?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Yes, I am a French student. Is Bethany a French student?

Class: No, Spanish.

Instructor (to Bethany): Bethany, are you a Spanish student?

Bethany: Yes, I am a Spanish student.

Instructor: That's right. What does Anita study?

A couple of things to note here. We are orbiting the fact that someone "is a student". When I address the class, I often use the word "class" to start my sentence. I want to make it clear whom I am addressing. When I talk to a student directly, I use their name. Sometimes beginning learners still get flustered and speak out anyway, but this basic system eliminates most confusion.

The second thing to note is that learners probably don't have much in the way of vocabulary regarding academic subjects. You can get around this by having students shout out academic subjects using the L2 phrase "how do you say [insert academic subject]?".

Take your time with this and let students come up with a ton of options. Then decide three or four things that Anita studies. Through your discussion, you find that Anita studies Spanish, art, and math.

Instructor: Class, Anita studies Spanish, art, and math. Does Anita have a biology class?

Class: No.

Instructor: Does Anita have an art class?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Does Anita have a Spanish class or a geology class?

Class: She has a Spanish class.

Instructor: That's right, she doesn't have a geology class. She studies Spanish, art, and math. Who in our class studies art?

Petra: I study art.

You can take a momentary detour from the story to talk about someone in your class. In this case, Petra has volunteered some information. The key to acquisition is that you continue the flow of CI in a low-pressure setting. As long as learners are interested, engaged, and comprehending, there is nothing wrong with a detour like this. Talking about a student will increase buy-in, build community, and demonstrate to learners the relevance of using L2 to communicate.

Instructor: Petra studies art. Petra, do you like your art class?

Petra: Yes, I like it.

Instructor: Class, Petra likes her art class. Is it your favorite class?

Petra: No, it's not my favorite.

Instructor: Of course not! Your favorite class is [Spanish]! Is your favorite course [Spanish], Petra?

Petra: Yes, my favorite course is [Spanish].

Instructor: So, you have an art class, and you like it, but your favorite class is [Spanish].

Petra: Yes.

Instructor: Class, Petra has an art class, and she likes it. But her favorite class is [Spanish]. Who else has an art class?

Frank: I have an art class.

Instructor: Frank, you have an art class?

Frank: Yes.

Instructor: Do you like your art class?

Frank: No.

Instructor: You don't like your art class?

Frank: No.

Instructor: Frank has an art class but doesn't like it. Does Petra have an art class?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Does Petra like her art class or does Frank like his art class?

Class: Petra.

Instructor: That's right. Petra likes her art class, but Frank does not like his art class. Class, what do you think? Does Frank like [Spanish] class?

Jonathan: No!

Instructor (fake indignant): No?!? Of course he does! Everybody likes [Spanish]!

As you can see, this sidetrack provides a steady stream of CI for learners. We haven't made any additional progress in our story, but that's not a problem. The goal is not to race through a story, and you get no prize for finishing a story in two days. These detours are windows into the lives of our students and are therefore incredibly valuable.

Whether they admit it or not, most people like to talk about themselves. If we can get students to open up about themselves, we can get to know them, build community, and continue the flow of CI in this context. Done correctly, these detours are all we need to help learners acquire the language. Now, let's get back to our story with a smooth transition and a quick review.

Instructor (feigning a poor memory): What does Anita study again?

Class: Math.

Instructor: Math, and what else?

Class: Art and Spanish.

Instructor: Oh, that's right. Anita studies Spanish, art, and math. How old is Anita?

Class: 22.

Instructor: Yes, she's 22. And where is she from?

Class: Vienna.

Instructor: Whom does she live with? Her mom or her grandma?

Class: Her grandma.

Instructor: How old is her grandma?

Class: 85.

Instructor (again feigning a poor memory): She's 85? She's not 86?

Petra: She's 85!

Instructor: She is?!

Petra: Yes!

Instructor: Oh, okay. She's 85. Anita is 22?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Is Anita a professor or a student?

Class: Student.

Instructor: Okay, great. So, there is a young woman. Her name is Anita. She is from Austria and lives in Vienna, which is the capital of Austria. Anita is 22 years old. She lives with her 85-year-old grandma. Anita is a university student and has three classes: Spanish, art, and math.

A quick review gets us back on track to continue the story. This helps us to not leave anyone behind, and the additional repetitions seem fresh(ish) to students because of our detour.

Instructor: What time is Anita's math class at?

Jonathan: 11 a.m.

Instructor: Class, Jonathan says that Anita's math class is at 11 a.m. Is it at 11 a.m.?

Petra: No, it's at 10 a.m.

Instructor: Petra, you say that Anita's math class is at 10 a.m.?

Petra: Yes.

Instructor: Class, is Petra right? Is Anita's math class at 10 a.m.? Or is Jonathan right? Is Anita's math class at 11 a.m.? Let's vote. Raise your hand if you want the class to be at 10 a.m..

*Seven people vote*

Instructor: Seven people want the class to be at 10 a.m. Raise your hand if you want the class to be at 11 a.m.

*13 people vote*

Instructor: It looks like 13 people want Anita's math class to be at 11 a.m. (And several people abstained from voting)

Instructor: Okay, Anita's math class is at 11 a.m.

This detail is not important to the story, but it is a great way to show telling time in context. I will be honest; students may not be thrilled about learning things like telling time in L2. After a few more orbiting questions, we determine that Anita's Spanish class is at 12 p.m. and her art class is at 10 a.m. Now we have her basic schedule sketched out, which is a task I want learners to be able to say by the end of teaching this story.

At this point I'm probably a little burnt out if I am the instructor Also, I am probably a little tired if I am a learner. This process is intense, and in a typical 50-minute class period, I will only plan for 20-30 minutes of storytelling, although you can do more if there are brain breaks involved. We're probably pushing up against that number right now if we have not exceeded it already. We will pick this up again tomorrow.

If you plan on using a Word document to summarize your story, now is the time to do another review. Simply open a Word document and project it on the screen. Start at the beginning of your story and ask a bunch of rapid-fire questions. Write the answers in your Word document. Crank the font size up so learners in the back can see it easily. They can write it down if they want, or they can just watch. In my experience, learners love this part of class because they see and hear the whole story summarized in five minutes.

Let us imagine that we have a 50-minute class period7 and are picking up from where we left off yesterday. You will notice that our story to this point looks similar to our script, but differs in many key ways. The character's name is different, as are the character's age and place of origin. It can get quite confusing, especially if you have more than one section where you are teaching the same story. If you assigned a student to write out a version of the story or summarized as a class the day before, you are in good shape on this front. Simply refer to your summary as needed.

I pull out the class artwork. It is roughly half done to this point since we are only halfway through the story. We review the story by asking and answering orbiting questions about the artwork. Recycling this information is critical for learners to acquire the language in the story. The trick here is getting them to actively try to remember the language that they used yesterday. Once we get to a point in where learners are comfortable and seem to remember the story, we use our orbiting questions to slingshot our CI rocket ship into the next part of the story.

Instructor: On Friday, Anita is at home. Is Anita at home?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Is Anita at school?

Class: No.

Instructor: Is Anita at home or at the hospital?

Class: At home.

Instructor: That's right, Anita is at home. Am I at home?

Class: No.

Instructor: I don't live at this school?

Class (not having any of my cheekiness today): No.

Instructor: No, I don't live at this school. Am I at home or at school?

Class: At school.

Instructor: That's right, I'm at school. Is Anita at school?

Class: No.

Instructor: Where is Anita?

Class: At home.

Instructor: Exactly! I am at school and Anita is at home. What time is it in the story

Frank: 9 a.m.

Jonathan: 10 a.m.

Instructor: Is it 9 a.m. or 10 a.m.?

*A small discussion about the time ensues. Fortunately, Petra speaks up and the instructor uses her answer to move things along.*

Petra: It's 9 a.m.

Instructor: Petra is right. It's 9 a.m. It's 9 a.m. and Anita is at home. She thinks: Oh no! I have to go to class! Does Anita want to go to class?

Class: No! %p Instructor: No, of course not. Who wants to go to class? Anita does not want to go to class. Anita doesn't want to go to class because she is nervous.

At this stage of the script there is some information that I will not personalize for each class. It is not that we are not able to improvise different stories. In fact, we could easily come up with different reasons why Anita doesn't want to go to class. Maybe her “ex” is in the class, and it is awkward between them. Perhaps her favorite singer is having a concert. This story could go in a million different directions and for the purposes of CI, that's totally fine. Just be aware that you may not be able to target specific vocabulary if you leave stories this open-ended.

If you have enough time with students, it will not matter if you target sets of vocabulary or not. Eventually, you can introduce it in context when it comes up a week, month or even six months from now. In my current teaching situation, I have approximately 10 weeks with my learners and I am bound to my scope I outlined in the planning stages of my course. With this in mind, I will direct the story in a certain direction to guarantee that we cover certain topics – academic subjects – in this case.

Notice that in this part I use fewer orbiting questions. By presenting a few statements in a row I am driving the narrative forward in a specific direction. Once that has been accomplished, I can begin my line of questioning again.

Instructor: Anita is nervous. Why is Anita nervous to go to class?

Jonathan: How do you say "bully" in [Spanish]?

Instructor: "Bully". Anita is nervous because there's a bully at school? Maybe... it's possible.

Since I am trying to guide students with these questions, I'm going to politely reject Jonathan's answer. I appreciate his participation, but it's not where I want to guide the story. Many students will guess where I want this story to go because of the TPR phrase "she has a difficult test". Petra is going to do just that because she is the rock of our class (pun very much intended).

Petra: She has a difficult test. %p Instructor: That's exactly right! Nice work, Petra. Anita is nervous to go to class because she has a difficult test. Does Anita have a difficult test or an easy test?

Class: Difficult.

Instructor: Yes, Anita has a difficult test. Petra, do you have a difficult test?

Petra: No.

Instructor: Oh, class, Petra doesn't have a difficult test. Does Anita have a difficult test?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: Yes, Anita has a difficult test. Do I have a difficult test?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, that would be ridiculous. I'm the instructor I don't have tests. Do I want to take a test?

Class: No.

Instructor: You're right. I don't want to take a test. Does Anita want to take a test?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, she doesn't want to take a test. Why doesn't she want to take a test?

Frank: She's nervous.

Instructor: That's right, Frank. Anita doesn't want to take a test because she's nervous. Why is she nervous? Is she nervous because the test is easy?

Class: No, the test is hard.

Instructor: Correct! Anita doesn't want to take the test because she is nervous, and she is nervous because the test is difficult. What class is the test in?

Frank: Math.

Jonathan: Art.

Petra: Spanish.

Instructor: Hmm... let's vote.

*The class votes for math*

Instructor: Class, Anita's has a math test. Does Anita have a science test?

Class: No.

Instructor: No, she doesn't have a science test. Does she have a math or a Spanish test?

Class: She has a math test.

Instructor: Good, she has a math test. What time is her math test?

Class: 11 a.m.

Instructor: Yes, the test is at 11. What time is it now?

Class: It's 9 a.m.

Instructor: Okay, perfect. Anita is nervous because she has a difficult math test at 11 a.m. Right now, it is 9 a.m. and Anita is at home. She thinks: Oh no! I have a difficult math test at 11 a.m. I don't want to take my math test! It's too hard! I need to think of a good excuse. It's true. Anita needs to come up with a good excuse. Finally, Anita thinks of a good excuse. She can't go to class because.... Why not? Why can't Anita go to class? What excuse does Anita think of?

This is another time where I have taken charge of the driving the story forward. I do a brief recap of the portion of the story we just orbited and then took us in the direction I want to go. While I want to guide the story in a certain direction, I do not want this to be entirely my story. Some personalization will give learners a sense of ownership of this story. It is a balance, and the excuse the character thinks up is the perfect detail to personalize since it will completely change the ending of the story. It could be a believable excuse or one that is so far-fetched no one would ever believe it, which could be the difference between a comedy and a tragedy. With the choice left up to the learners, they feel empowered to use the language for self-expression, decision-making, and for creating art (yes, this story is art). The learners pick up on the utility of the language, if only subconsciously, and I'm sure this has a positive effect on their acquisition.

We're almost done with our story, so let us get back to it.

Instructor: Anita doesn't want to go to school today because she has a difficult math test. What excuse does Anita think of?

Jonathan: How do you say "Her dog ate her homework?" in [Spanish]?

Instructor: In [Spanish] you say, "Her dog her dog at her homework". Class, did Anita's dog eat her homework? It's a possibility...

Frank: She's in the hospital.

Instructor: Frank, you say that Anita's excuse is that she is in the hospital?

Frank: Yes.

Instructor: Class, is Anita's excuse that she's in the hospital?

Class: Yes.

Instructor: My, oh my! What an excuse!

Petra (remembering our TPR phrase): She's sick.

Instructor: Petra, is that part of the excuse too? Anita is in the hospital because she's sick?

Frank: She's dead.

*The class laughs because Frank is being a clown. Roll with it*

Instructor: Her excuse is that she's in the hospital because she's dead?

Frank: Yes.

Petra (remembering a story detail from before): She's not very smart.

Instructor: Oh, that's right. She's not very smart, Anita.

This story has moved from “normal” to the absurd. Not all stories need to be absurd, but they often end up there. The absurd details are like inside jokes with a group of friends. The learners tend to love them, but they will not be at all funny to the outside world. This is community building in action. Of course, the story doesn't have to be humorous, but I lean toward clean humor whenever appropriate. The goal is to lower people's affective filter, to make them feel comfortable, and give them sense of belonging. By satisfying these criteria you enable CI to work its magic.

Instructor: So, Anita thinks of an excuse. She can't go to class to take her difficult math test because, she says she's sick, I mean she says she's dead. Nope, she's not very smart. How does Anita talk to her professor?

Justine: Email.

Petra: Fax.

Frank: Phone call.

We're running out of time int he class, and the story is almost over. I'm just going to pick my favorite answer.

Instructor: Ooooo, Frank. You're right. Anita takes out her phone and calls her professor. He answers.

*The instructor quickly acts out an improvised dialog from the details sketched out to this point. The instructor plays the parts of both the professor and Anita*

Instructor (Professor): Hello?

Instructor (Anita): Hello, professor? This is Anita from your 11am math class. I know there is a test today, but I can't go to class.

Instructor (Professor): Why not?

Instructor (Anita): I have a really good excuse.

Instructor (Professor): What is it?

Instructor (Anita): I can't go to class because I'm in the hospital.

Instructor (professor): You're in the hospital? Are you okay?

Instructor (Anita): No, I'm sick. No, I mean... I'm dead.

At this point the class is howling with laughter. It is an absurd and hilarious situation. Not only that, but learners are also getting a dopamine hit for understanding this whole discussion in L2. Such a moment will stick with learners, and it is not uncommon for them to make references to Anita and her terrible excuse at some point down the road.

With the story fully created, you can pull out your Word document and summarize the story with learners. Now you will have a rough draft that will make writing a complete version much easier.

Other things to consider

Student Actors

Another wrinkle you can throw into the mix is adding student actors to your story. These students will act out the story as you co-create it, and you will act as the director. If they are not animated enough, that is fine. Just stop the "play", give some directions in easy-to-understand L2, and start back up again by repeating the line. You might have to do this several times because students might not think you are serious. This has been the case when I have tried this. They just feel embarrassed, or something, but the important thing is the visual representation of the spoken language and the sense of community the acting builds.

When a line comes up that learners need to speak, you can just let them repeat after you. Give them a couple of seconds, but if they get stuck or mess up, help them with the answer by writing it on the board. Tell them that it is normal to say something a native speaker would not necessarily say. You want to reduce the pressure learners perceive as much as possible in order to lower the affective filter.

If you are orbiting a sentence and there is a student actor, ask the actor a question. This adds more repetitions to the orbiting cycle and allows you to use other forms of the same verb.

Instructor: I want an elephant. Jessica, do you want an elephant?

Jessica: No, I don't want an elephant.

Instructor: Class, Jessica doesn't want an elephant.

HUMOR

The goal of every story is not to be absurd or funny. Humor is not strictly necessary for CI storytelling to be successful. Stories can be sad, romantic, suspenseful, nostalgic, or a combination of various styles.

Furthermore, The Beginning Storyteller is not generally a stand-up comedian. Still, humor is heavily associated with a basic human emotion: happiness. In the best of cases, humor leads to genuine laughter. It is a desirable aspect of community building and being in a loving community lowers the affective filter. In turn, this opens the door for CI to do its magic.

Do not be afraid to laugh with your students. Obviously, I would caution against laughing at any student, and in particular any student that may feel out of place in a language classroom. But there are many situations where laughter is appropriate and will greatly enhance your CI storytelling experience.

CHECKING COMPREHENSION

Incomprehensible language raises the affective filter. It is uncomfortable to process language you cannot easily understand. Most language classes fail to teach someone to speak a new language because comprehension is low, and the affective filter is high. Therefore, it is important to make sure learners are understanding the story as you go along. When I was a Beginning Storyteller, I made the mistake of telling a story without checking comprehension. When I got to the end of my story, about half the class was completely lost. What a waste of time!

You can deal with this in two main ways. First, check the body language of students. Read their faces and look for the "deer in the headlights stare". The other way is to put the responsibility of comprehension squarely on the shoulders of learners. When you notice that a learner is not comprehending, speak with them after class, especially if they've never had [Spanish] before. Ask them how they are doing and encourage them to stop you if they feel lost.

Since I teach at the college, I often get students who have never had a formal Spanish class in their whole lives. I let them know that learning a new language is hard work and that it becomes impossible if they don't understand or don't understand at a high enough level. I tell them that I would rather stop and repeat a sentence an extra five times than leave anyone behind.

Learners can easily fake comprehension for a while. As the stories become more complex, however, it becomes painfully apparent who has been faking it. Although learners do not have to understand every single word to acquire language, it is the most efficient use of time if learners are in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). This is what Krashen is referring to the idea of “i + 1”, which is the learners’ level of input plus a little language beyond their current level of acquisition. puts them in “flow state”, where time dilates and passes quickly. It is as if the learners forget they are processing messages in a new language. Note that if we give “i + 2”, “i + 10” or “i + 100”, we break the flow state. Checking learners’ comprehension allows to modify input to help them stay in the ZPD for as long as possible.

ADDING NEW 'IN-BOUNDS' VOCABULARY AS NECESSARY

Sometimes it is nice for learners to provide details in the story. It is possible for The Beginning Storyteller to have complete control over the story, and in a sense you do. But giving learners the chance to participate in the creation of the story by deciding key details about the characters and plot makes the story much more meaningful to them.

Lesson 3 Worksheet

Get more out of this lesson by completing its companion worksheet .